Being as rare as they are, Carbon Stars are incredibly mysterious.

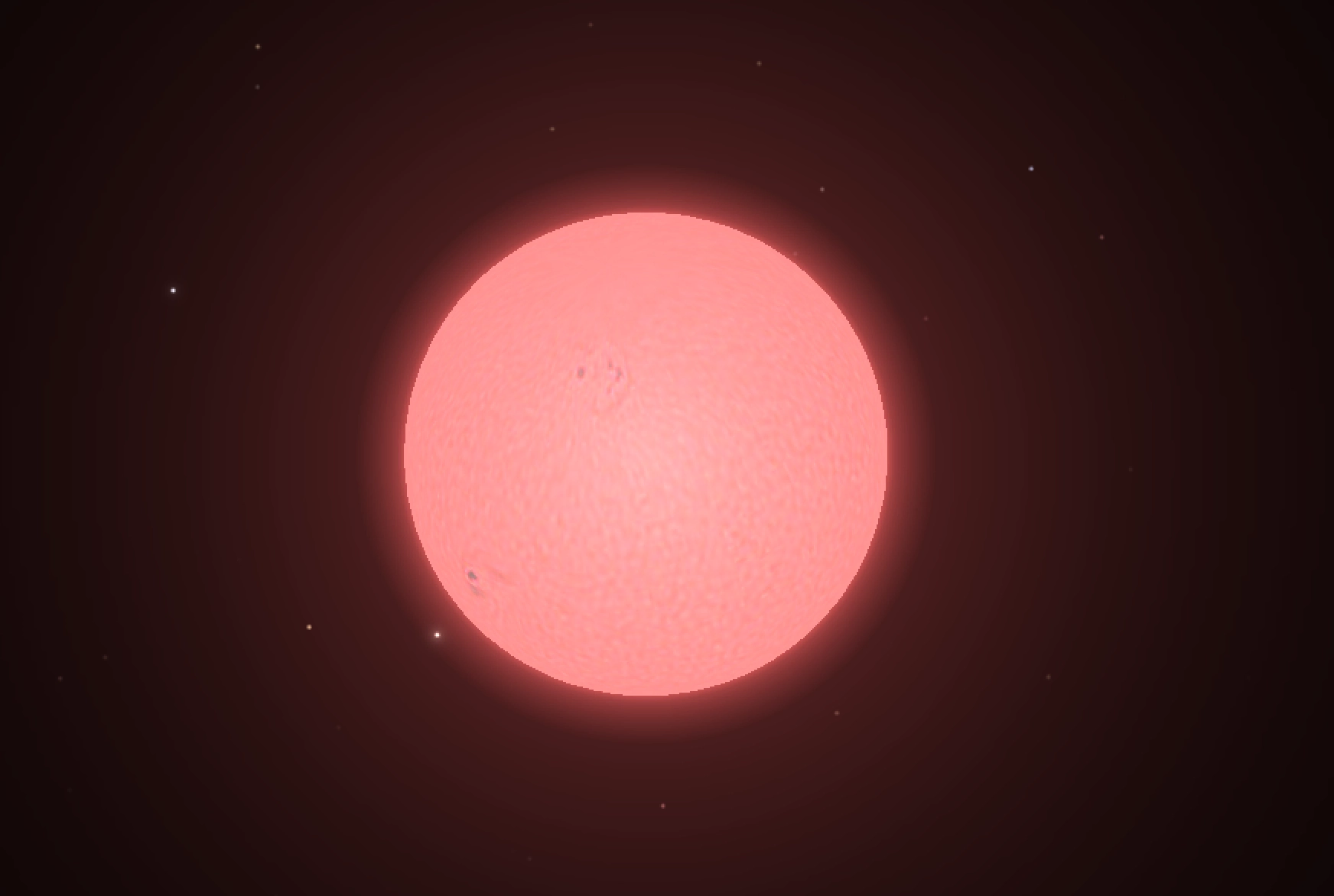

A star’s Red Giant phase can be divided into many, many stages. From the Red Clump to the Subgiant, the possibilities for starry-eyed researchers can be endless. As the star draws closer to its death, moving to and fro in its turbulent asymptotic stage, it turns into a Carbon Star (or C Star) - shining a hue of brilliant red.

After the main-sequence progenitor star has exhausted its’ supply of helium, it moves to its’ Asymptotic Giant Branch, where it’s brightness and size begins to fluctuate as it ‘pulsates’, shrinking suddenly then puffing back out, typically larger than it was before. As the energy produced by fusion in the core becomes more and more spread out over the ever-increasing surface area of the star, there is the same amount of energy being produced, but there is a larger surface area for the energy to radiate from, so the star shines a hue of brilliant red. Towards the end of this stage, turbulent pulsations along with a large, almost solar-wind like outer envelope can allow these giants to turn into some of the coolest stars in the Universe, with temperatures bottoming at 2600 Kelvin, barely hotter than the coldest Red Dwarfs!

Since these stars are close to giving up their outer layers and becoming white dwarves, they’re also surrounded by a halo of dust, formed when the products from their core are mixed into the outer layers through convection in a “dredge-up” event and then lost due to solar winds. As this nuclear ash moves further away from the star it cools and condenses into a dusty cloud. This dust tends to block starlight, leading to variations in the brightness of the star.

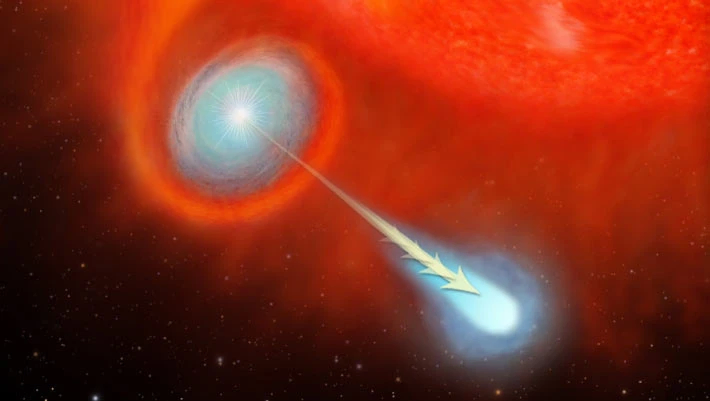

V Hydrae (or just V Hya for short) is probably one of the most famous carbon stars. This star appears to be shooting out bullets of plasma every eight or so years, which has so far puzzled scientists - despite having a really, really fast solar wind (at around 15 km/s), the jets are being shot at velocities of around 200 km/s, almost as fast as our sun moving around the galaxy! There’s ample evidence to suggest these jets are caused by a faint companion obscured by the larger one; this phenomenon does take place pretty regularly in periods of about eight years, and it’s possible that another star’s gravitational influence would clump material into jets.

One day, our sun’s going to look like these stars, bloated, red, dying. Even then, we’re going to have to wait 4.5 billion years for that to happen, so right now it’s probably best to just sit back and watch these bloated, deep red stars live out the remainder of their lives.

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.