With Tsuchinshan-Atlas making its grand getaway from the Solar System, there’s no doubt that the world’s telescopes, cameras, phones are all pointed upwards - for once. Engagement in astronomy’s almost at a record high, with social media bursting with images of the comet, a blurry streak often in the midst of city lights - there’s no doubt that there’s someone in some corner of the Earth looking at these photos starry-eyed.

Now, comets are icy rocks - leftovers from the formation of the Solar System either flung way out by the gravity of the planets, or have migrated inwards by interacting with objects that have also formed far, far out. These are asteroids - only that their water ice hasn’t been vaporised by the radiant power of the sun - instead, they’re so far away that the sun’s not powerful enough to do so for most of its orbit. There are technically some “stragglers” that count as “comets” (looking at you, Phaethon!)

When a comet draws closer to the sun, their icy surface “crack” - they vaporise under the radiant power of the sun, and with nowhere to go, the gases shoot out of all orifices of the stars with bright, bright jets. This is what we typically see as a “comet’s tail” - the result of millions of water droplets reflecting the light of the sun. Comets like C/1996 Hale-Bopp, C/2011 Lovejoy - there’s been a ton of these rocks that enter the inner solar system once every billion years, seeing the sun only 10 times before it inevitably burns out. These are the “C” comets - ‘long-period’ comets with orbital periods upwards of 200 years (meaning that it takes them more than 200 years to finish 1 orbit) - contrasted with the “P” comets - short-period comets with orbital periods of less than 200 years (examples include Eros and Halley’s Comet! See you at 2061.)

Mind you, these icy bodies can also persist far out, staying in moderately circular orbits and remaining icy. Examples are like the Kuiper Belt, the mishmash of objects past Neptune just before the outer solar system. However, other belts of these objects exist - including the Centaurs.

These icy rocks orbit anywhere between Jupiter and Neptune. Loosely defined, a “Centaur” is just an orbiting body that doesn’t really belong to any class of asteroid, or Kuiper Belt object for the matter. Unlike the famous icy dwarf planets of Pluto, Eris, Makemake and Haumea, the Centaurs are typically not large enough to be rounded spheres - where the gravity at the center of mass of the body is strong enough to force the surface of the body to be a sphere.

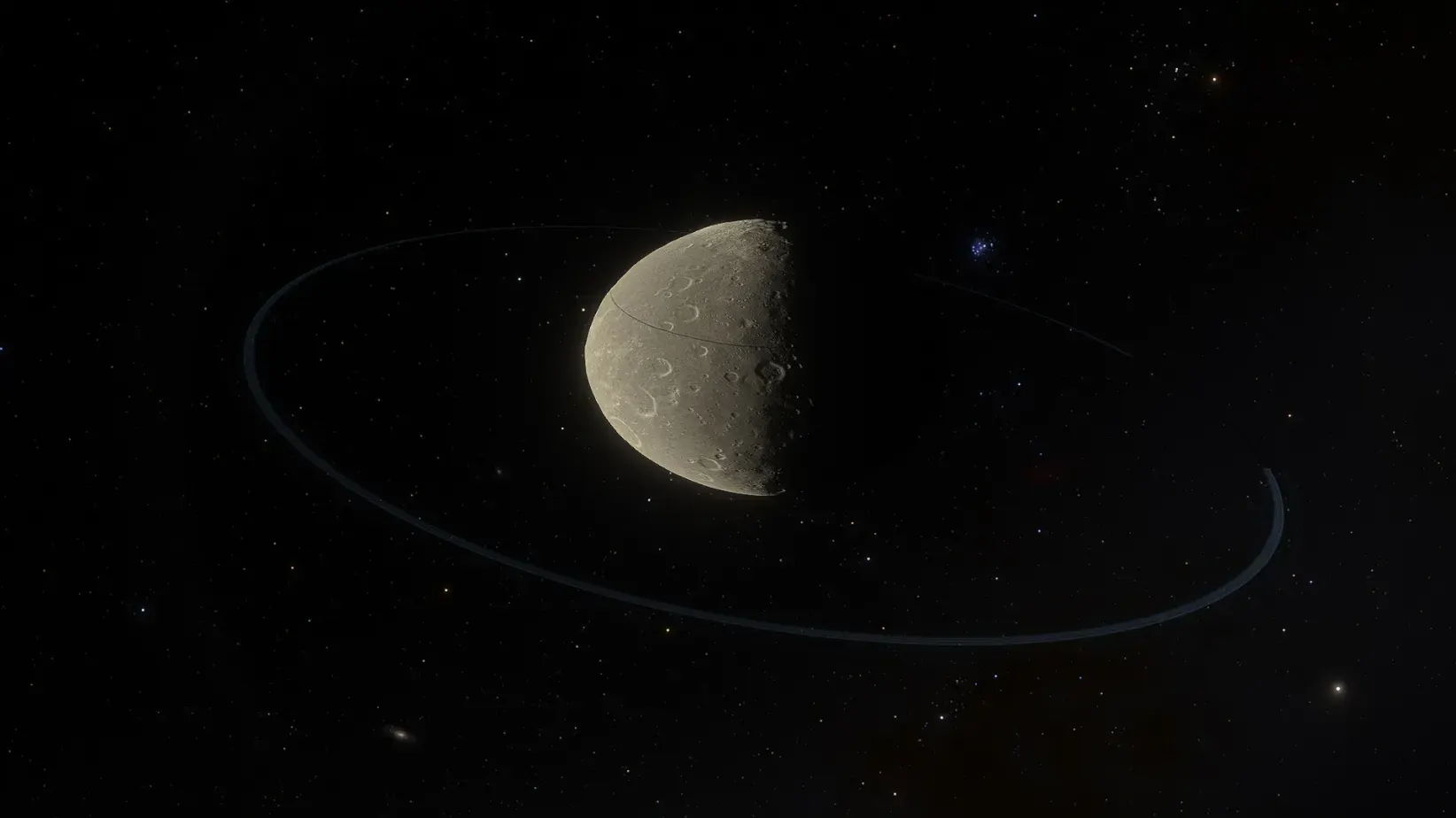

These “Centaurs”, much like the asteroid belt, have sizes ranging from scales of metres to hundreds of kilometres. The largest one, 10199 Chariklo, is one of interest - it’s two rings are an enigma, with it being one of the smallest objects we’ve discovered rings around, it’s been a great object to study over the years. In 2013, where Chariklo momentarily passed in front of a background star, dimming its light and outlining its own features. This let us discover the rings orbiting 250 and 400 kilometres from the surface of the Centaur.

These icy objects, though far-flung, are viewed with interest by many on our planet - it’s theorised that many of these objects are the origins of the long-period comets, being flung out by the gravity of the gas planets when these objects draw close to them. The water on Earth’s theorised to also come from these objects - the movement of the outer planets back during the early solar system could’ve sent some of these ‘ice rocks’ hurtling towards our planet, giving us our first oceans as the ice sublimed into our atmosphere from the impact.

Some day, there’ll be a mission to these far-flung objects, studying their chemistry to verify our water hypotheses. But until then, we’ll watch these dim objects drift through our solar system, each one drifting with oceans of water under their icy veneers.