Star explodes, material collapses inwards, and lo and behold! A black hole is formed. Large, primordial cloud of neutral hydrogen collapses inwards on itself at the dawn of the universe, a supermassive black hole is created. Needless to say, black holes come in all shapes and sizes. From the biggest, baddest quasars to the 10-kilometer stellar mass ones, there’s a great spectrum of sizes that black holes fit into.

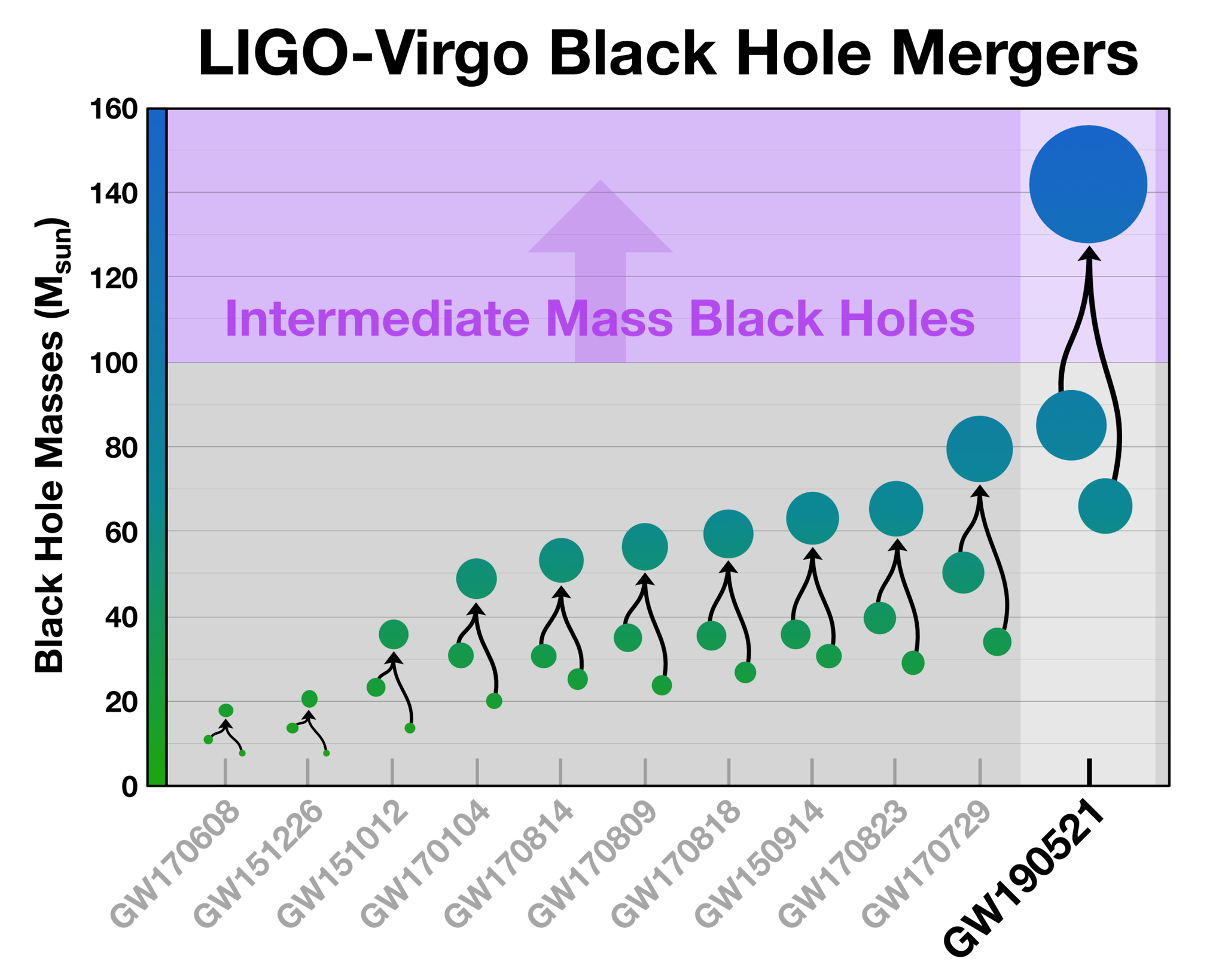

However, when you plot the black holes that make up this spectrum side-by-side and compare the masses of the black holes we’ve already discovered, you’ll notice something.

The gap in the centre of the graph are known as the intermediate-mass black holes (ImBHs), theorised to occupy the mass gap between their supermassive and stellar-mass counterparts. Our models say they should exist - we just haven’t been able to detect them.

There are many reasons to why ImBHs remain so elusive. To start, there just aren’t that many of them. Some of the models we have for ImBH formation all point to very slow stellar-mass black hole mergers in dense environments, such as in globular clusters, large groups of stars (give numbers) that seem to share a common center (link). In this dense environment, stars, white dwarfs, black holes and other objects interact with each other more often, as their gravitational regions of influence overlap more often. Not all interacting black holes merge or consume other stellar objects to grow; most are flung out or settle into new orbits, often in distinct oval shapes known as ellipses. As a result, there’s no guarantee that an ImBH will be created in a globular cluster, making them even rarer.

Plus, to directly image a black hole, it has to be large enough so that our cameras can distinguish them from their surroundings. With most globular clusters already pretty far from us, such as M4, the closest cluster at almost 5,500 light years away, the small sizes of lower-mass black holes can make them very difficult to image. Most stellar black holes we’ve discovered involve looking at the background of space to which it moves across; if a black hole is placed in front of a background star or galaxy, the image of that background object is warped and its light amplified. This is known as microlensing - the magnification of light as it rounds a black hole’s gravitational well.

Sometimes, you can see news articles talking about a ‘brand-new discovery’ of an intermediate-mass black hole. They’re usually referring to the evidence that compels the best and brightest of the field to believe they’d made the breakthrough. Sometimes, as per (LINK 3) this Hubble article, it can be because of certain motions in stars around an ‘invisible’ dot; where the black hole’s gravity leads to odd, often highly elliptical orbits around an invisible point in space. Other times, it may be free gas clouds that have these eccentric orbits, remnant material from the formation of these dense clusters quenched before they are able to form any stars.

Regardless of what comes of this research, these objects are likely to be stellar in nature, with tons of new models for their formation still to be tested. These objects have captivated astrophysicists’ attention, that’s for sure - and in the future, this attention is likely to result in a breakthrough.

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.