Save for its name, Uranus isn’t really the most memorable planet out there. Being far enough away from Earth that any amateur observer would barely be able to make out coherent details of its surface, let alone the very faint bands and storms that any self-respecting gas giant would have. As a result, astronomical focus has typically been on its slightly smaller sibling, Neptune.

Uranus is most famed for its unique axial tilt. It’s 97 degrees from it’s centre, meaning the planet orbits sideways. As a result, the planet essentially rolls forward in its’ orbit, mimicking a tidal locking effect. Uranian seasons each span a quarter of its orbit, so during winter, one side of the planet faces completely away from the sun while the other stares straight into the sun’s light. Mean temperatures on Uranus hover around -195 degrees Celsius, the coldest in the solar system. It’s theorised that Neptune has an internal mechanism of sorts keeping it warm, perhaps due to a higher pressure per unit area as Neptune is also much denser than Uranus.

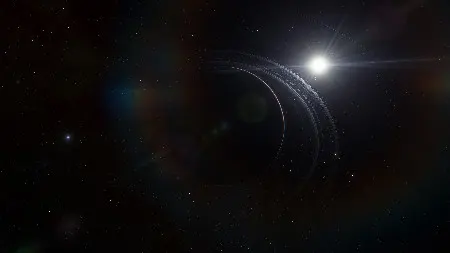

Like any self-respecting gas giant, Uranus has its own (very!) faint ring and moon system, albeit the least massive among the Jovian planets. The system consists of 13 inner moons, 5 large moons and 9 irregular moons. It’s theorised that the rings of Uranus, especially the brighter, inner rings, are replenished through collisions between inner moons; the system itself is unstable and many moons are expected to crash into each other in the near future, which would release ejecta, replenishing the ring. Each of the larger moons orbit outside of the inner moons, while the irregular moons are theorised to be Centaurs (asteroid-like objects orbiting between the Kuiper and Asteroid Belts) that have been captured by Uranus.

Some Uranian Moons, like their counterparts orbiting Uranus’ cousins, may have differentiated interiors! Titania and Oberon, the two largest moons in the system, are suspected of harbouring underground oceans, like in Europa or Ganymede, but on a much smaller scale, existing only in a termination zone between an icy mantle and a rocky core. Besides, this water would be incredibly, incredibly salty, essentially being a very large brine pool. Even if Uranus’ tidal forces heated up the interior of the planet, our chances of finding life would be slim.

Uranus isn’t blue by choice! It’s atmosphere is primarily made of hydrogen and helium, with a smattering of methane, water and ammonia. The same methane that makes up Uranus creates its bright blue colour, as it has absorption lines in the early to deep infrared, allowing it to absorb red light. UV light from the sun can also break down molecules, creating organic compounds that lead to a dense, thick haze surrounding the planet.

Perhaps there was a reason to give Uranus its name, the methane atmosphere and all. Besides, this planet’s also garnered attention for diverting from the standard Roman naming convention for planets. Now that I think of it, “Caelus” does sound much better than Uranus…

Like what you see? Feel free to subscribe to our blog to receive updates whenever we post.